Soy and Cancer Risk: Busting Myths with Scientific Evidence

- Dec 17, 2025

- 7 min read

What is Soy?

Soy is a versatile legume that forms the basis of many foods, particularly in Southeast Asian diets. It is consumed in various forms including whole soybeans like edamame, soy drinks, tofu, and fermented products such as tempeh and miso. Additionally, soy is widely used in alternative milks and yogurts (1).

Nutritional Facts About Soy

Soy is nutritionally rich, providing B vitamins, fibre, potassium, magnesium, and high-quality protein. Unlike many plant proteins, soy protein is a complete protein, containing all nine essential amino acids that must be obtained from the diet. Soy foods can be fermented or unfermented. Fermentation involves culturing the soy with beneficial bacteria, yeast, or mould, which may improve digestibility and nutrient absorption by partially breaking down sugars and proteins (2).

What Are Isoflavones?

Isoflavones are a class of phytoestrogens, naturally occurring plant compounds that can bind to oestrogen receptors in the body and induce weak estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects (3). These compounds are found in soy as well as other plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, grains, tea, and wine. Isoflavones include genistein and daidzein, which are particularly concentrated in soy. Due to the wide diversity of phytoestrogens and differences in metabolism, bioavailability, and pharmacological activity, it is complex to determine their precise health effects without large, long-term intervention studies (3).

Why the Confusion?

Soy’s effects on the body are influenced by many factors:

Type of study: Animal studies may not fully reflect human metabolism of soy. (2)

Hormone levels: Soy’s oestrogen-like activity can vary depending on circulating hormone levels. For example, in premenopausal women, soy may act anti-estrogenically, while in postmenopausal women, it may have weak estrogenic effects. Hormone-sensitive cancers also respond differently based on receptor status. (2)

Type of soy: Whole foods, processed soy products, fermented vs. unfermented forms, or supplements containing isoflavones versus soy protein can all act differently in the body (2).

This complexity has led to misunderstandings about soy and its safety.

How Isoflavones Work

Soy contains natural plant compounds called isoflavones (mainly genistein and daidzein). These isoflavones have a chemical structure that is similar but not identical to human oestrogen. Because of this, they can bind to oestrogen receptors (ERs) in the body — particularly ER-β, which they bind to more strongly than ER-α (4,5).

Weak estrogenic activityWhen oestrogen levels in the body are low (e.g., post-menopause), soy isoflavones can mildly activate oestrogen receptors — but their potency is 1,000–10,000 times weaker than human oestrogen (5). This weak activation is why they may help with symptoms like hot flushes in some women.

Anti-estrogenic activityWhen oestrogen levels are high, soy isoflavones can compete with stronger endogenous oestrogen for receptor binding. Because they are much weaker, they can reduce oestrogen signalling in these conditions (4,6) This is why soy foods are considered safe — and possibly protective — for people with a history of hormone-sensitive cancers.

In simple terms, Soy isoflavones can attach to oestrogen receptors. They act like very weak oestrogens, so depending on the body’s hormone environment, they can either gently mimic oestrogen (low-oestrogen states) or block stronger oestrogen from binding (higher-oestrogen states).

Myth 1: Soy Raises Oestrogen and Causes Cancer

Large studies suggest otherwise. The Shanghai Women’s Health Study (7) followed over 73,000 women for more than seven years and found that:

High soy intake before menopause reduced breast cancer risk by 59%.

Adolescent soy consumption reduced risk by 43%.

No link was found between soy intake and postmenopausal breast cancer.

Additionally, a 2024 study (8) found that soy isoflavones may reduce breast cancer recurrence in postmenopausal women and those with hormone receptor-positive tumours, particularly at daily intakes of close to 60 mg. While promising, soy is not a treatment, and further research is needed.

Myth 2: Soy is Bad for Men’s Hormones

Evidence consistently shows that soy does not affect male hormone levels. A 2009 meta-analysis found that neither soy foods nor isoflavone supplements changed testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, free testosterone, or free androgen index in men. Some studies also suggest that higher soy intake may be associated with lower prostate cancer risk in men (9).

Soy and Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer rates are higher in Western countries than in Asia. Migrants who adopt Western diets show increased risk, while those who maintain traditional diets do not. Eight clinical trials showed some reduction in prostate cancer risk with soy or isoflavone supplementation, though no changes in PSA levels were observed. (10)

A meta-analysis of 30 studies confirmed that soy intake is linked to reduced prostate cancer risk, with genistein and daidzein acting as weak oestrogens in prostate tissue. (11)

Myth 3: Soy is Ultra-Processed

While many soy-based meats and milks are classified as ultra-processed foods (UPFs), this does not necessarily reflect their nutritional quality. Compared with animal-based products, they:

Deliver high-quality protein.

Are not inherently high in energy density, sugar, or fat.

Nutrient content varies by fortification, protein, and fat source.

Consumers should check labels for protein content, sugar levels, sodium, and fortification. Processing level alone is not a reliable indicator of nutritional value (12).

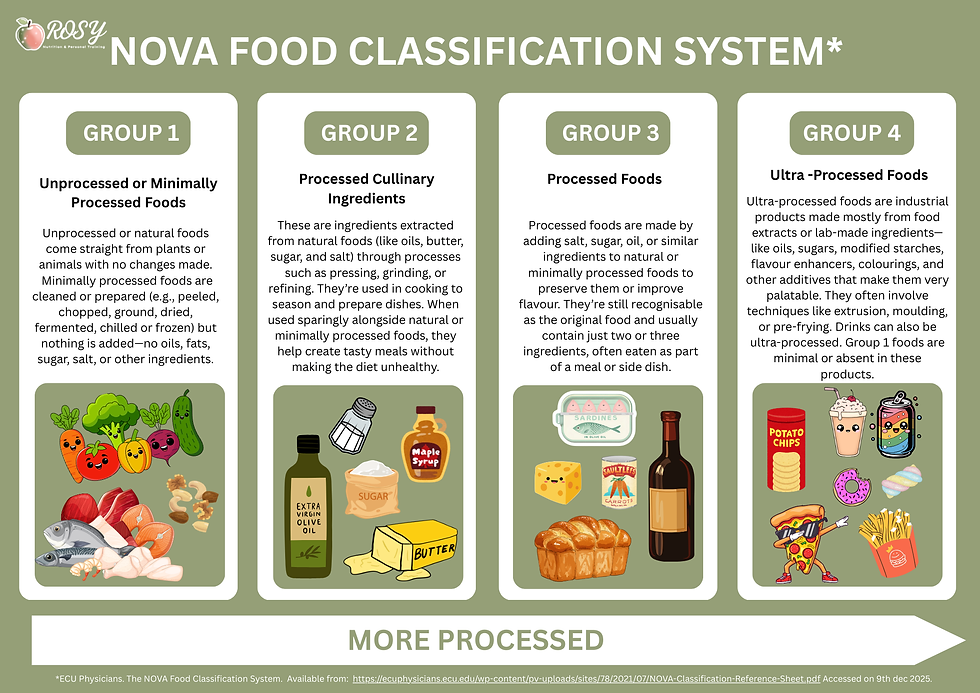

Understanding UPFs.

To understand ultra-processed foods properly, we need to look at the NOVA Food Classification System (13), created by researchers at the University of São Paulo. NOVA groups foods based on how much and why they’re processed, helping us make clearer choices about the foods we eat every day. Below is a simple graphic breakdown (14) of the four groups — and exactly where ultra-processed foods fit in.

This doesn’t mean you must completely avoid UPFs — but knowing what ultra-processed foods are helps you make informed, confident choices that support better digestion, stable energy and long-term health. If you build most meals from Group 1 and Group 2 foods, include some Group 3 foods, and reduce Group 4 foods, you’re already making a huge difference to your nutrition.

Comparing Soy Products

Checking labels helps you identify less-processed options. When examining the ingredients of soy-based alternatives—whether it’s plant-based chicken or veggie sausages—there are usually clues that indicate whether a product leans more toward being an ultra-processed food. Some tips for selecting better options include:

Choose ingredients you recognise: Prefer items that you could realistically have in your kitchen, rather than additives like thickeners or stabilisers.

Think of the NOVA classification system: Select products that contain a higher proportion of group 1 and 2 foods.

Opt for a shorter ingredient list: Fewer ingredients usually mean less processing.

Look for natural flavourings: Ingredients labelled as natural flavourings are preferable to vague terms like “flavourings.”

Myth 4: Soy is Bad for Thyroid Function

According to the British Dietetic Association’s fact sheet on soy (1), soy does not harm normal thyroid function. Soya can interfere with levothyroxine absorption (levothyroxine is a medication used to treat hypothyroidism), so if you are taking levothyroxine you should try to avoid soya; if you do wish to include it, you should leave as long as possible (at least four hours) between eating soya and taking the medication (15).

A meta-analysis of 18 randomised controlled trials found that although soy supplements raised thyroid-stimulating hormone levels slightly, they did not affect actual thyroid hormone production (16). Additionally, the American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) Committee on Nutrition concluded that evidence for adverse effects of dietary soya isoflavones on human development, reproduction, or endocrine function is not conclusive (17).

Conclusion

Soy is a nutrient-dense food with a long history of safe consumption. Many common myths—including effects on hormones, cancer risk, processing level, and thyroid function—are not supported by current evidence. Isoflavones in soy have weak estrogenic activity that can be beneficial in some contexts, and soy-based foods provide high-quality protein for both men and women. Choosing minimally processed soy products and understanding individual health needs can help integrate soy safely into a balanced diet.

References

1. BDA. Soya Foods and Your Health. [online] Available from: https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/soya-foods.html Accessed: 8 Dec 2025.

2. Harvard Education. Straight Talk About Soy. [online] Available from: https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/soy/ Accessed: 8 Dec 2025.

3. Bacciottini L, Falchetti A, Pampaloni B, Bartolini E, Carossino AM, Brandi ML. Phytoestrogens: food or drug? Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2007 [online] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2781234/#sec14 Accessed: 25 Oct 2025.

4. George G. J. M. Kuiper, Bo Carlsson, Kaj Grandien, Eva Enmark, Johan Häggblad, Stefan Nilsson, Jan-Åke Gustafsson. Comparison of the Ligand Binding Specificity and Transcript Tissue Distribution of Estrogen Receptors α and β. Endocrinology, Volume 138, Issue 3, March 1997, Pages 863–870. [online] Available from: https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.138.3.4979 Accessed on 8 Dec 2025

5. Messina MJ, Wood CE. Soy isoflavones, estrogen therapy, and breast cancer risk: analysis and commentary. Nutr J. 2008 Jun 3;7:17. [online] Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1475-2891-7-17 Accessed on 8 Dec 2025.

6. Rietjens IMCM, Louisse J, Beekmann K. The potential health effects of dietary phytoestrogens. Br J Pharmacol. 2017 Jun;174(11):1263-1280. [online] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5429336 Accessed on 8 Dec 2025.

7. Lee SA, et al. Adolescent and adult soy food intake and breast cancer risk: results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. 2009. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19403632/ Accessed 25 Oct 2026.

8. M Diana van Die, PhD , Kerry M Bone, BSc(Hons) , Kala Visvanathan, MD, MHS , Cecile Kyrø, PhD , Dagfinn Aune, PhD , Carolyn Ee, PhD, Channing J Paller, MD. Phytonutrients and outcomes following breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. (2023) [online] Available from: Accessed: https://academic.oup.com/jncics/article/8/1/pkad104/7468128 8 Dec 2025.

9. Jill M Hamilton-Reeves, Gabriela Vazquez, Sue J Duval, William R Phipps, Mindy S Kurzer, Mark J Messina. Clinical studies show no effects of soy protein or isoflavones on reproductive hormones in men: results of a meta-analysis. (2009) [online] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19524224/ Accessed 8 Dec 2025.

10. van Die MD, Bone KM, Williams SG, Pirotta MV. Soy and soy isoflavones in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BJU international. 2014 May;113(5b):E119-30. [online] Available at: https://bjui-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bju.12435 Accessed on 9th dec 2025

11. Applegate CC, Rowles JL, Ranard KM, Jeon S, Erdman JW. Soy consumption and the risk of prostate cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2018 Jan 4;10(1):40. [online] Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/1/40 Accessed on 9th dec 2025.

12. Messina M, et al. The health effects of soy: A reference guide for health professionals. [online] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.970364/full. Accessed 25 Oct 2026.

13. ECU Physicians. The NOVA Food Classification System. Available from: https://ecuphysicians.ecu.edu/wp-content/pv-uploads/sites/78/2021/07/NOVA-Classification-Reference-Sheet.pdf Accessed on 9th dec 2025.

14. Rosy Nutrition & PT. What Are Ultra-Processed Foods? A Guide to Understanding the NOVA Food Classification. [Online] Available from: https://www.rosynutritionandpt.com/post/what-are-ultra-processed-foods-a-guide-to-understanding-the-nova-food-classification Accessed 12 Dec 2025.

15. British Thyroid Foundation. Diets and supplements for thyroid disorders. [online] Available from: https://www.btf-thyroid.org/diets-and-supplements-for-thyroid-disorders#di4 Accessed 8 Dec 2025.

16. Otun J, Sahebkar A, Östlundh L, Atkin SL, Sathyapalan T. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of soy on thyroid function. Scientific reports. 2019 Mar 8;9(1):1-9. [online] Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-40647-x Accessed 8 Dec 2025.

17. Bhatia J, Greer F; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Use of soy protein-based formulas in infant feeding. Pediatrics. 2008 May;121(5):1062-8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0564. PMID: 18450914. [online] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18450914/ Accessed 8 Dec 2025.

Comments